Some cool two shot plastic parts china images:

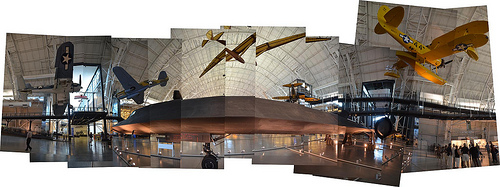

Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center: Photomontage of SR-71 on the port side

Image by Chris Devers

Posted via email to ☛ HoloChromaCinePhotoRamaScope‽: cdevers.posterous.com/panoramas-of-the-sr-71-blackbird-at…. See the complete gallery on Posterous …

• • • • •

See far more pictures of this, and the Wikipedia write-up.

Particulars, quoting from Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum | Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird:

No reconnaissance aircraft in history has operated globally in much more hostile airspace or with such total impunity than the SR-71, the world’s fastest jet-propelled aircraft. The Blackbird’s performance and operational achievements placed it at the pinnacle of aviation technology developments for the duration of the Cold War.

This Blackbird accrued about 2,800 hours of flight time for the duration of 24 years of active service with the U.S. Air Force. On its final flight, March six, 1990, Lt. Col. Ed Yielding and Lt. Col. Joseph Vida set a speed record by flying from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., in 1 hour, 4 minutes, and 20 seconds, averaging three,418 kilometers (two,124 miles) per hour. At the flight’s conclusion, they landed at Washington-Dulles International Airport and turned the airplane more than to the Smithsonian.

Transferred from the United States Air Force.

Manufacturer:

Lockheed Aircraft Corporation

Designer:

Clarence L. "Kelly" Johnson

Date:

1964

Country of Origin:

United States of America

Dimensions:

All round: 18ft 5 15/16in. x 55ft 7in. x 107ft 5in., 169998.5lb. (five.638m x 16.942m x 32.741m, 77110.8kg)

Other: 18ft five 15/16in. x 107ft 5in. x 55ft 7in. (five.638m x 32.741m x 16.942m)

Supplies:

Titanium

Physical Description:

Twin-engine, two-seat, supersonic strategic reconnaissance aircraft airframe constructed largley of titanium and its alloys vertical tail fins are constructed of a composite (laminated plastic-sort material) to lessen radar cross-section Pratt and Whitney J58 (JT11D-20B) turbojet engines function massive inlet shock cones.

Long Description:

No reconnaissance aircraft in history has operated in a lot more hostile airspace or with such complete impunity than the SR-71 Blackbird. It is the fastest aircraft propelled by air-breathing engines. The Blackbird’s functionality and operational achievements placed it at the pinnacle of aviation technology developments throughout the Cold War. The airplane was conceived when tensions with communist Eastern Europe reached levels approaching a full-blown crisis in the mid-1950s. U.S. military commanders desperately necessary correct assessments of Soviet worldwide military deployments, specifically near the Iron Curtain. Lockheed Aircraft Corporation’s subsonic U-two (see NASM collection) reconnaissance aircraft was an able platform but the U. S. Air Force recognized that this fairly slow aircraft was currently vulnerable to Soviet interceptors. They also understood that the fast development of surface-to-air missile systems could place U-two pilots at grave danger. The danger proved reality when a U-two was shot down by a surface to air missile more than the Soviet Union in 1960.

Lockheed’s initial proposal for a new higher speed, higher altitude, reconnaissance aircraft, to be capable of avoiding interceptors and missiles, centered on a style propelled by liquid hydrogen. This proved to be impracticable due to the fact of considerable fuel consumption. Lockheed then reconfigured the design and style for traditional fuels. This was feasible and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), already flying the Lockheed U-2, issued a production contract for an aircraft designated the A-12. Lockheed’s clandestine ‘Skunk Works’ division (headed by the gifted style engineer Clarence L. "Kelly" Johnson) made the A-12 to cruise at Mach 3.two and fly nicely above 18,288 m (60,000 feet). To meet these difficult specifications, Lockheed engineers overcame a lot of daunting technical challenges. Flying far more than 3 occasions the speed of sound generates 316° C (600° F) temperatures on external aircraft surfaces, which are enough to melt conventional aluminum airframes. The design and style group chose to make the jet’s external skin of titanium alloy to which shielded the internal aluminum airframe. Two standard, but really strong, afterburning turbine engines propelled this outstanding aircraft. These power plants had to operate across a massive speed envelope in flight, from a takeoff speed of 334 kph (207 mph) to more than 3,540 kph (2,200 mph). To avert supersonic shock waves from moving inside the engine intake causing flameouts, Johnson’s team had to style a complicated air intake and bypass system for the engines.

Skunk Works engineers also optimized the A-12 cross-section style to exhibit a low radar profile. Lockheed hoped to attain this by meticulously shaping the airframe to reflect as small transmitted radar energy (radio waves) as feasible, and by application of unique paint created to absorb, rather than reflect, those waves. This therapy became one of the first applications of stealth technologies, but it by no means fully met the design and style ambitions.

Test pilot Lou Schalk flew the single-seat A-12 on April 24, 1962, soon after he became airborne accidentally for the duration of higher-speed taxi trials. The airplane showed excellent promise but it required considerable technical refinement just before the CIA could fly the first operational sortie on Might 31, 1967 – a surveillance flight more than North Vietnam. A-12s, flown by CIA pilots, operated as component of the Air Force’s 1129th Special Activities Squadron below the "Oxcart" plan. Whilst Lockheed continued to refine the A-12, the U. S. Air Force ordered an interceptor version of the aircraft designated the YF-12A. The Skunk Works, nevertheless, proposed a "specific mission" version configured to conduct post-nuclear strike reconnaissance. This method evolved into the USAF’s familiar SR-71.

Lockheed constructed fifteen A-12s, such as a special two-seat trainer version. Two A-12s were modified to carry a specific reconnaissance drone, designated D-21. The modified A-12s have been redesignated M-21s. These were created to take off with the D-21 drone, powered by a Marquart ramjet engine mounted on a pylon between the rudders. The M-21 then hauled the drone aloft and launched it at speeds high enough to ignite the drone’s ramjet motor. Lockheed also constructed three YF-12As but this variety never ever went into production. Two of the YF-12As crashed for the duration of testing. Only one particular survives and is on show at the USAF Museum in Dayton, Ohio. The aft section of one particular of the "written off" YF-12As which was later utilized along with an SR-71A static test airframe to manufacture the sole SR-71C trainer. A single SR-71 was lent to NASA and designated YF-12C. Like the SR-71C and two SR-71B pilot trainers, Lockheed constructed thirty-two Blackbirds. The initial SR-71 flew on December 22, 1964. Simply because of intense operational charges, military strategists decided that the more capable USAF SR-71s should replace the CIA’s A-12s. These had been retired in 1968 soon after only one year of operational missions, mostly more than southeast Asia. The Air Force’s 1st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron (component of the 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing) took more than the missions, flying the SR-71 starting in the spring of 1968.

After the Air Force started to operate the SR-71, it acquired the official name Blackbird– for the particular black paint that covered the airplane. This paint was formulated to absorb radar signals, to radiate some of the tremendous airframe heat generated by air friction, and to camouflage the aircraft against the dark sky at higher altitudes.

Experience gained from the A-12 system convinced the Air Force that flying the SR-71 safely necessary two crew members, a pilot and a Reconnaissance Systems Officer (RSO). The RSO operated with the wide array of monitoring and defensive systems installed on the airplane. This gear integrated a sophisticated Electronic Counter Measures (ECM) system that could jam most acquisition and targeting radar. In addition to an array of advanced, higher-resolution cameras, the aircraft could also carry equipment created to record the strength, frequency, and wavelength of signals emitted by communications and sensor devices such as radar. The SR-71 was created to fly deep into hostile territory, avoiding interception with its tremendous speed and high altitude. It could operate safely at a maximum speed of Mach three.three at an altitude far more than sixteen miles, or 25,908 m (85,000 ft), above the earth. The crew had to put on pressure suits equivalent to these worn by astronauts. These suits were required to shield the crew in the occasion of sudden cabin stress loss whilst at operating altitudes.

To climb and cruise at supersonic speeds, the Blackbird’s Pratt & Whitney J-58 engines have been created to operate constantly in afterburner. Although this would seem to dictate higher fuel flows, the Blackbird actually achieved its best "gas mileage," in terms of air nautical miles per pound of fuel burned, throughout the Mach 3+ cruise. A standard Blackbird reconnaissance flight may need many aerial refueling operations from an airborne tanker. Each and every time the SR-71 refueled, the crew had to descend to the tanker’s altitude, typically about six,000 m to 9,000 m (20,000 to 30,000 ft), and slow the airplane to subsonic speeds. As velocity decreased, so did frictional heat. This cooling impact caused the aircraft’s skin panels to shrink considerably, and those covering the fuel tanks contracted so considerably that fuel leaked, forming a distinctive vapor trail as the tanker topped off the Blackbird. As soon as the tanks were filled, the jet’s crew disconnected from the tanker, relit the afterburners, and once again climbed to high altitude.

Air Force pilots flew the SR-71 from Kadena AB, Japan, throughout its operational career but other bases hosted Blackbird operations, also. The 9th SRW sometimes deployed from Beale AFB, California, to other areas to carryout operational missions. Cuban missions were flown straight from Beale. The SR-71 did not start to operate in Europe till 1974, and then only temporarily. In 1982, when the U.S. Air Force primarily based two aircraft at Royal Air Force Base Mildenhall to fly monitoring mission in Eastern Europe.

When the SR-71 became operational, orbiting reconnaissance satellites had currently replaced manned aircraft to collect intelligence from internet sites deep within Soviet territory. Satellites could not cover every single geopolitical hotspot so the Blackbird remained a important tool for international intelligence gathering. On several occasions, pilots and RSOs flying the SR-71 provided info that proved important in formulating productive U. S. foreign policy. Blackbird crews offered critical intelligence about the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and its aftermath, and pre- and post-strike imagery of the 1986 raid carried out by American air forces on Libya. In 1987, Kadena-primarily based SR-71 crews flew a number of missions over the Persian Gulf, revealing Iranian Silkworm missile batteries that threatened commercial shipping and American escort vessels.

As the efficiency of space-based surveillance systems grew, along with the effectiveness of ground-primarily based air defense networks, the Air Force began to lose enthusiasm for the costly plan and the 9th SRW ceased SR-71 operations in January 1990. Regardless of protests by military leaders, Congress revived the system in 1995. Continued wrangling more than operating budgets, however, soon led to final termination. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration retained two SR-71As and the a single SR-71B for higher-speed research projects and flew these airplanes until 1999.

On March 6, 1990, the service career of a single Lockheed SR-71A Blackbird ended with a record-setting flight. This particular airplane bore Air Force serial quantity 64-17972. Lt. Col. Ed Yeilding and his RSO, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Vida, flew this aircraft from Los Angeles to Washington D.C. in 1 hour, 4 minutes, and 20 seconds, averaging a speed of 3,418 kph (2,124 mph). At the conclusion of the flight, ‘972 landed at Dulles International Airport and taxied into the custody of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. At that time, Lt. Col. Vida had logged 1,392.7 hours of flight time in Blackbirds, far more than that of any other crewman.

This certain SR-71 was also flown by Tom Alison, a former National Air and Space Museum’s Chief of Collections Management. Flying with Detachment 1 at Kadena Air Force Base, Okinawa, Alison logged a lot more than a dozen ‘972 operational sorties. The aircraft spent twenty-four years in active Air Force service and accrued a total of 2,801.1 hours of flight time.

Wingspan: 55’7"

Length: 107’5"

Height: 18’6"

Weight: 170,000 Lbs

Reference and Further Reading:

Crickmore, Paul F. Lockheed SR-71: The Secret Missions Exposed. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1996.

Francillon, Rene J. Lockheed Aircraft Given that 1913. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1987.

Johnson, Clarence L. Kelly: More Than My Share of It All. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985.

Miller, Jay. Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Operates. Leicester, U.K.: Midland Counties Publishing Ltd., 1995.

Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird curatorial file, Aeronautics Division, National Air and Space Museum.

DAD, 11-11-01

Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center: Photomontage of Overview of the south hangar, such as B-29 “Enola Gay” and Concorde

Image by Chris Devers